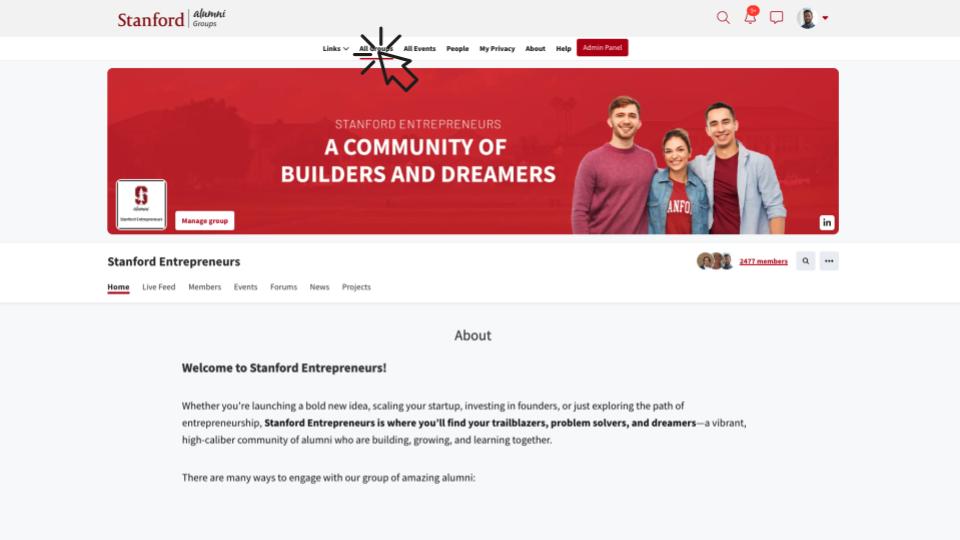

By Diva Sharma, Founder of Cognitio Labs & Board Member, Stanford Entrepreneurs

Venture capital investor Kinga Stanislawska, founder of European Women in VC, the largest community of female venture and growth managers across Europe, and entrepreneur Roberta Lucca, co-founder of BAFTA-awarded game developer Bossa Studios, speak with Diva Sharma, inventor of a remote patient monitoring device, Stanford’21 graduate to share how more women can be encouraged to build successful businesses based on their own stories. All three were presentors at the European Union Horizon 2020 Conference Conference in Brussels, Belgium.

Across industries, women remain underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. A Microsoft Research study conducted in 2024 found that while many girls develop an interest in STEM around the age of 11, that enthusiasm often declines sharply by age 15. The issue, therefore, is not a lack of curiosity but a lack of sustained encouragement, representation, and confidence during formative years.

Early Exposure and the Power of Purpose

Despite early self-doubt about her technical abilities, Lucca eventually discovered how technology particularly games could be used for social impact. “I tried to change my career many times and failed at many new projects I started,” Lucca reflects. “However, by taking the risk to start new ventures, I also learnt to become more resilient. Technology inspires me to create my own future, not just consume it.”

That mindset led her to co-found Bossa Studios, a Britain-based, BAFTA-awarded game development company best known for Surgeon Simulator, which has amassed over two million downloads worldwide.

From her perspective as a founder and mentor, Lucca sees early education as a critical lever for change. While mentoring aspiring developers on national television, she observed how few young women felt comfortable stepping into technical roles. She emphasizes that communities must normalize girls’ participation in STEM from an early age through game jams, collaborative learning, and peer exchange.

Lucca also points to the role educators and parents play in sustaining interest. She advocates for K–12 programs centered on “technology for good,” which highlight how scientific skills can address real-world challenges. Such programs, she believes, help young girls connect learning with purpose and build confidence in their ability to turn ideas into ventures.

The Capital Gap Holding Women Back

While early encouragement is essential, structural barriers persist particularly in venture capital.

Kinga Stanislawska, founder of European Women in VC (EVC) and a member of the European Innovation Council, highlights a stark imbalance: less than 2% of global venture capital funding goes to women-founded startups, and only 5-15% of first checks are written by female investors.

When Stanislawska began her career, she struggled to find female investors within her network. In response, she founded EVC in 2017, building one of Europe’s largest communities of investors dedicated to funding female founded companies.

“I tend to invest in deep technology companies bringing unique infrastructure to solve some of the biggest challenges in the world,” Stanislawska explains. She is particularly drawn to mission driven founders working in underserved sectors such as women’s health. “There are several problems to solve that deliver value to the other 50% of the world’s population.”

There Is No Single Entry Point into STEM

Stanislawska challenges the notion that women must follow a strictly technical path to contribute meaningfully to startups or venture capital. Instead, she encourages young women to explore a variety of roles within deep tech companies.

“There is a need for a variety of roles to support emerging startup whether you’re in a lab, in marketing, or on the commercialization team,” she says. “What matters in the long run is understanding the mission of the company and the basic science behind its work.”

For those interested in venture capital, Stanislawska emphasizes the importance of learning how capital shapes innovation and not shying away from technical concepts even without a formal STEM background. Curiosity, she notes, is often more important than credentials.

Building Confidence Through Real-World Impact

My own journey echoes many of these insights. As a teenager, I was hesitant to speak up in science classes that lacked female representation. That changed when my grandfather experienced a health scare. Motivated to solve a tangible problem, I began developing and later patenting a remote patient monitoring device focused on improved distress tracking.

Participating in local science competitions helped me build the confidence to share my work with policymakers and global leaders, including at the European Union Horizon 2020 Conference. That experience reinforced a key lesson shared by both Lucca and Stanislawska: confidence grows when young women see how their skills can create meaningful societal impact.

Looking Forward

At any stage of life, women can identify underserved problems they care deeply about and build or join ventures working to solve them. Whether through coding, research, design, storytelling, investing, or commercialization, there is no single path into STEM or entrepreneurship.

By fostering early exposure, emphasizing purpose-driven education, and widening access to capital and opportunity, we can ensure more women not only enter STEM fields but shape the future of innovation itself.